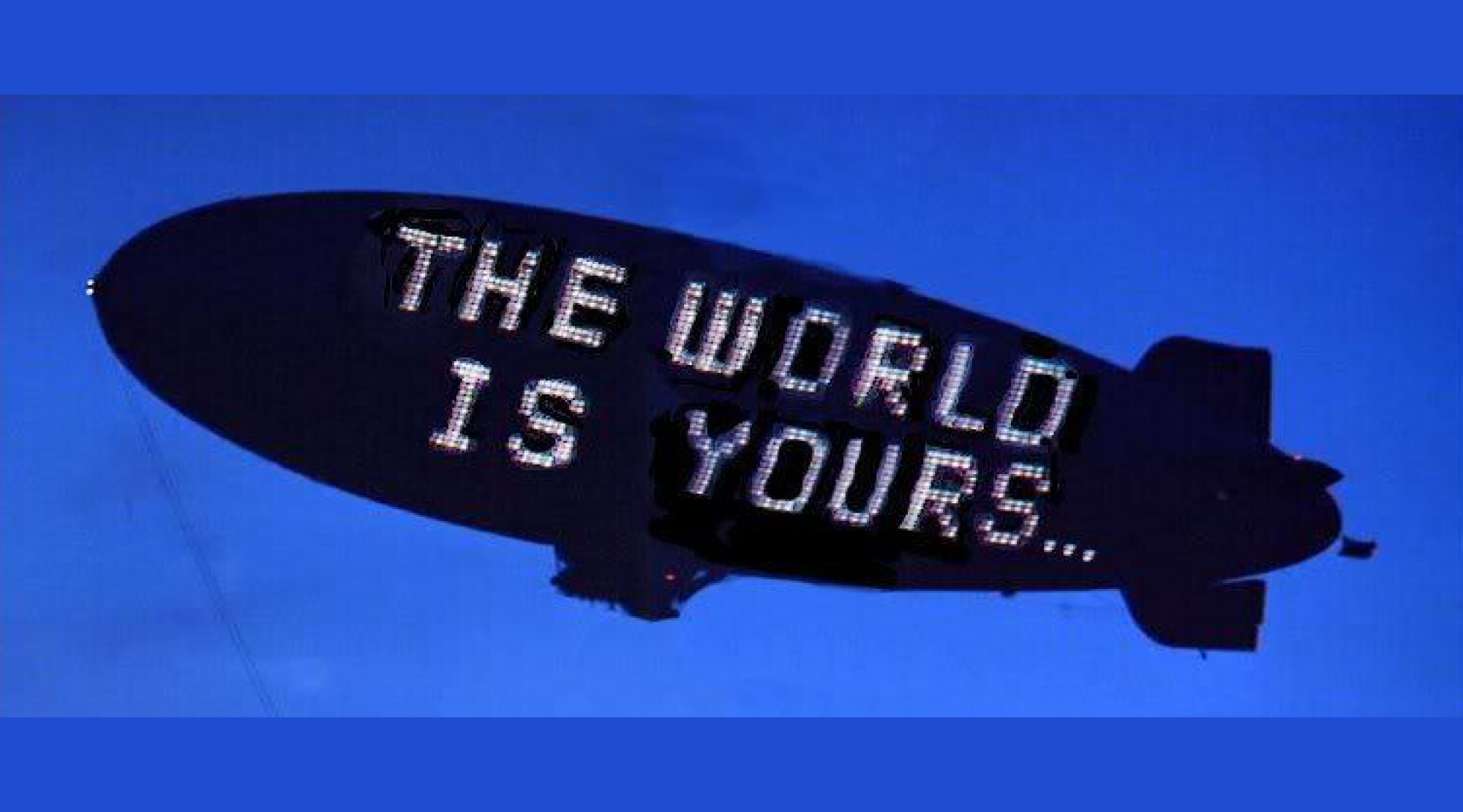

Whenever I hear the term global city, I picture a bloodied Al Pacino, machine-gun in hand, staring out the window of his tacky, over-the-top luxurious apartment, into a flying zeppelin displaying a text that says “The World is Yours.” It is a scene from the film Scarface, about a Cuban refugee named Tony Montana (played by Al Pacino), who arrives in the city of Miami in the 1980s. The film follows Tony rising through the criminal world of the city, and slowly, as he becomes more excessive and out of control, reaches his own demise. A classic story of greed and excesses, and the violence that comes with them. But why does this image come up? Is it somewhat representative of the characteristics of a global city? What is a global city anyway?

The term global city was coined by Saskia Sassen, as a concept to show the relation between the city and the process of globalization (Acuto, 2017). According to Sassen, in the age of global economy, the geographic dispersal of economic activities feeds the “growth and importance of central corporate functions” (Sassen, 2005). These corporate functions, in turn, becomes so complex that they are “subject to agglomeration economies” (Sassen, 2005), where they are outsourced to highly specialized firms clustered in some cities that can provide the infrastructure and network to run these complex central functions. These cities are then termed global cities, where they serve as the “primary node in the global economic network.”

This concept of global city “rapidly proliferates among urban practitioners” (Acuto, 2017). Over time, the concept becomes a status that is considered both desirable and beneficial. Many cities around the world want to be known as a global city, and local governments begin to promote their cities as global. In turn, many groups develop multiple methods to classify and rank cities – to distinguish between a global city and a non-global city, as well as to determine which one is “the most global” (Kearney, 2016).

One of these global city rankings is managed by A.T. Kearney, an American-based global management consulting firm (Atkearney.com). In their Global Cities report, the firm defines global city as a city “measured by its ability to attract and retain global capital, people, and ideas, as well as sustain that performance in the long-term” (Kearney, 2016). In order to capture this, the firm puts emphasis on “measuring city-level indicators to track progress” (Kearney, 2016). Using an array of indicators across different themes, such as business activity, human capital, political engagement, as well as personal well-being and innovation, the firm’s Global Cities identifies and ranks cities, where the top 15 are bestowed with the title “The Global Elite” (Kearney, 2016).

There are many other rankings of global cities, other than the one by A.T. Kearney. There is the Global Power Cities Index by the Institute for Urban Strategies, Cities of Opportunities index by PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Hot Spots 2025 by the Economist Intelligence Unit, to name a few. It is important to note that Sassen herself contributed to some of these rankings and surveys (Renn, Newgeography.com).

But is that what a global city really is? Is it really just about highlighting the ability of cities to compete in the global economy, as a marketing tool to promote cities?

Certainly some cities have benefited from being part of the global economy, with the coming in of foreign investments that boost industries, create jobs and contribute to the city’s wealth. But as cities become more economically successful in the global arena, inequality rises. Sassen herself mentions in her work that there are “growing inequalities between highly provisioned and profoundly disadvantaged sectors and spaces of the city” (Sassen, 2005). Global economy that these global cities are serving for are hurting a large portion of local economy. As Sassen puts it, “high prices and profit levels in the internationalized sector and its ancillary activities… have made it increasingly difficult for other sectors to compete for space and investments” (Sassen, 2009).

As infrastructures in cities are becoming more and more privatized and profit-driven to serve the multinational companies, foreign investors, as well as foreign tourists that bring in the big bucks, the technological advancement of the cities’ network of communication – transport, telecommunications, street, water and energy – have reached a higher level. However, they are only available for the ones who can afford them. From the setting up of fiber optic cables for faster Internet connection to the building of ‘smart’ highways to ease congestion, the construction of infrastructures are being catered to a specific affluent group of the society, while the other one is neglected (Graham, 2001).

The global city is not just a platform for global economy, but it also serves other cross-border networks – cultural, political, as well as criminal networks (Sassen, 2005). And we are seeing a rise in the latter lately. Take the city of Kuala Lumpur, for example. In the past year, the city has become the setting for two major assassinations. The first was the killing of a North Korean national by nerve gas, where the accused were of Indonesian and Vietnamese nationals. The second was the gunning down of a Palestinian scientist, where the family is blaming Mossad, the Israeli intelligence unit. Not to mention a few terror networks that are based in different parts of the globe, Kuala Lumpur included, where they recruit people from different nationalities, and orchestrate terror attacks at different major global cities around the world.

Suddenly the image of Al Pacino, stained with blood and machine-gun in hand, does not seem too far-fetched from reality. Tony Montana, the character he plays in the film, is of Cuban national, who flees his country in search of a better life, better economic opportunities. He ends up in Miami, working in the criminal “sector” in the city, where he deals with drug kingpins from Colombia, Puerto Rico, and the US itself. As he becomes successful and reaches the top, he becomes the target of these other competing drug lords. Coupled with his own greed and excesses, he meets his own terrible and fatal ending. Many cities around the world share a similar story with Tony Montana. Detroit and China’s ghost cities come to mind.

Does that mean cities should not be “global?” Going back to Sassen’s idea, global city is not merely a label or recognition for the city, but rather it is a concept that focuses on the city to understand the globalizing world (Sassen, 2005). Meaning it is not about whether the city needs to go global, to be put in the rankings, or to be recognized as more global than the other, or otherwise. Instead, it is about understanding that once a city is part of a global network – either economical, cultural, or criminal – it brings together a set of complexities that are part of the global intricacies, but manifested in city level. The city is the “terrain where multiplicity of globalization processes assume concrete, localized form” (Sassen, 2005). In turn, understanding and solving these complex issues on city level will help mitigate the problem on the global level.

Looking at it from this perspective, we can then see that the global city is not a category to be endorsed and replicated, but rather it is a construct to be explored and disentangled. In order to figure out how globalization is impacting contemporary lives, we need to see in what way do the flows and market “hit the ground” (Acuto, 2017). For Sassen, the street of the global city is where “new forms of the social and political can be recast and the transnational turbulence of our time expressed” (Acuto, 2017). In short, what the global city concept tells us is that solutions to our contemporary, globalized problems are out there, on the streets of our cities. By fixing our cities, we can fix our lives.

Badrul Hisham Ismail is the Program Director at IMAN Research.