There are many kinds of maps in the world: political maps show where one state’s power ends and another begins; physical maps show the relationship in the contours of the land, where mountain meets forest meets river meets ocean. Mapping, however, is not a politically neutral activity: by knowing these spatial relationships, we take the first step in taming and then changing these geographies.Then why not a social map? In this sense, a map would visually describe the social relationships of an imagined community. Two paintings at Patani Semasa, exhibited next to each other, explore and investigate how these artists perceive the relationships within the societies they’re embedded in. However, like maps, it is also the case that these paintings are not devoid of political purpose: what do we do with this mapped knowledge?

Jehabdulloh Jesorhoh’s They Way of Life of Malay Locals in Three Southernmost Provinces of Thailand seems to be clear in this respect. His other work displayed at Patani Semasa clue us in that Jehadulloh is on a mission to establish and represent a lost dignity of Malay-Muslims in Patani.

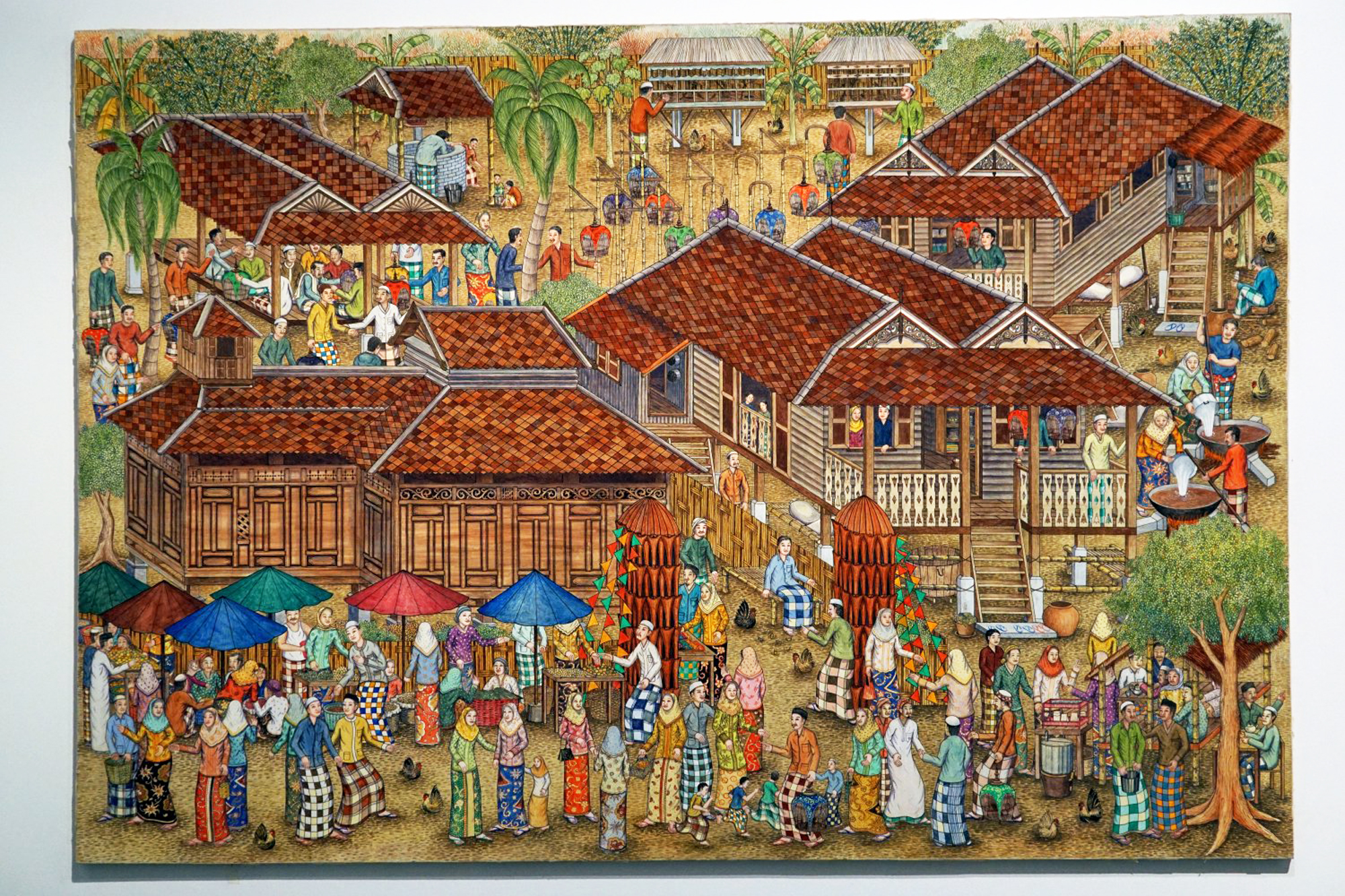

The representation of Malay-Muslim life as quiet, idyll and harmonious in The Way of Life entrenches this feeling. The Way of Life combines vignettes of private and public life in colours which are neither too vivid nor too earthy — an in-the-middle tone. It proudly represents the kampung life as a harmonious balance between the public and private, and between the traditional and the modern.

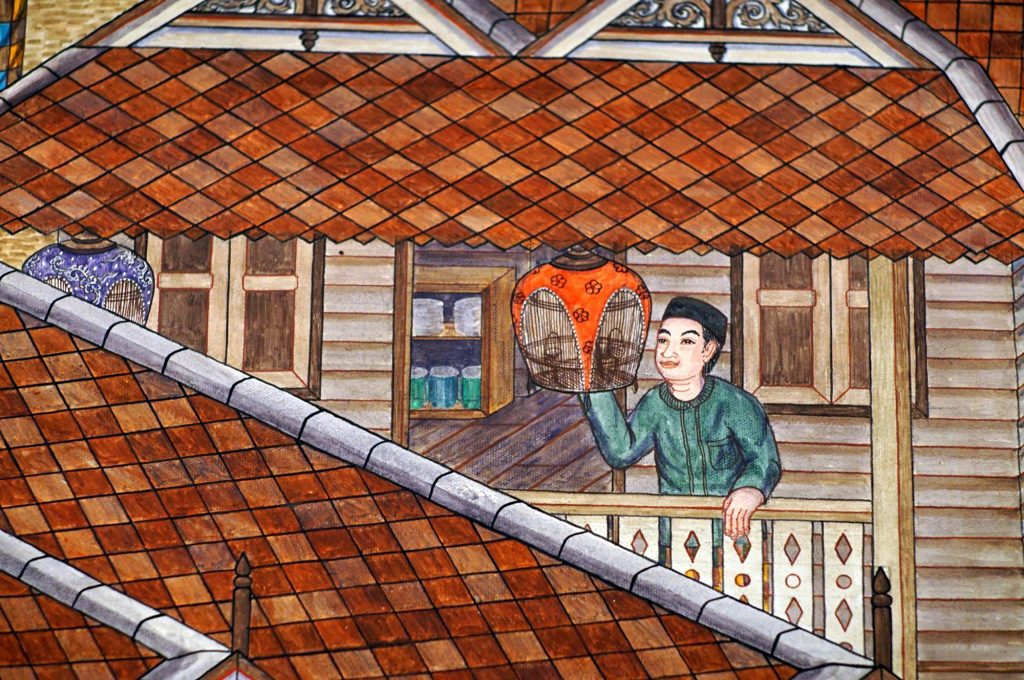

In the ‘foreground’ is a market where people walk, gather and trade. Chickens and children run about freely underfoot, while both wild trees and cultivated fruit trees grow at their leisure. The only real hint of modernity I could read was the bright red rack which could be plastic. Men and women gather under pavillions to have a carefree drink. But public life is not just about the self — on the side, men and women work together to prepare giant woks of food, ostensibly for the community as well. Men chat over the songs of birds in bird cages hung from bamboo poles. The repetition of second pavillion in the background emphasises the element of public, community life in the way of life.

Carvings and the particular Malay architecture style dominate the center left of the frame.

Alone, intimate, but seen and content.

Strangely dominating the center of the painting are two large houses: one facing the viewer, the other facing away. The former show people peeking out their houses, neither fearful nor hostile, but content to look on to the world. This underscores at least some kind of sufficiency with private space. The latter, however, is devoid of human presence. However, it prominently shows off the ornate woodwork of Malay traditional architecture, possibly highlighting its cultural importance amongst its people.

Finally, its Asian ‘linear’ perspective, which features a notable lack of a vanishing point, complements its similarity to a map. This map-likeness which puts every person at an equal size relative to the viewer hints at the equality of relationships between characters, with only the houses dominating the center of frame.

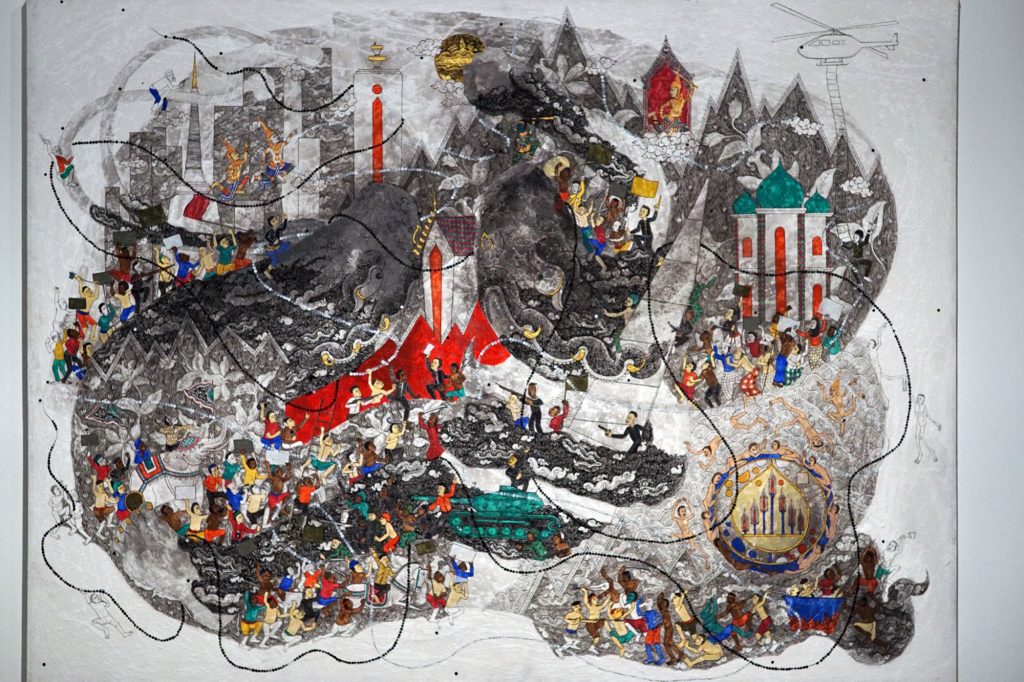

If Jehabdulloh’s The Way of Life is striking in its portrayal of harmony, Kokarot Sangnoy’s Movements on Turtle’s Back 1 is its diametric opposite in its portrayal of chaos. While it takes on a similar linear perspective to show off multiple vignettes of social situations, there is none of the orderliness found in The Way of Life. Streaks of bright red, blue and green inhabit a landscape dominated by black lines and white backgrounds.

A giant, black turtle writhes and curls upon itself as the inhabitants on its back wage war against each other, as it floats over Mount Meru. Two lengths of prayer rosaries, one white and one black, whip through the air, and flow and coil around the various vignettes. They perhaps symbolise the dual nature of good and evil that suffuse society. Figures straddling the outer limits of the turtle and close to the edge of the frame cling to the black beads and begin to lose their colour, perhaps symbolising their loss of humanity. Even the white of the background is not pure: it is in fact, criss-crossed with white paint.

Movements is one of the few pieces that inject the state and Buddhism, the official religion of Thailand back into the narrative. While in The Way of Life the buildings dominate the center of the frame, symbolic buildings rise from the folds of the turtle: a mosque on the right, a city on the left, and a temple in the centre.

Angry protestors gather at the base of these buildings: Muslims march towards the temple, but an uncoloured helicopter and a descending soldier approaches from behind. Men in suits holding up pieces of paper jockey for position in front of the central temple, but do not seem concerned with the periphery. Behind them are war elephant and tank, men with sword and men with machine guns; perhaps these are expressions of a clash or weaponisation of modernity and tradition. In the meanwhile, above the city are devas floating and leading yet another militant crowd.

Angry protestors in front of a mosque Top: Men in suits jockeying for position, supported by their own thugs.

Men in suits jockeying for position, supported by their own thugs.

The total effect of the two pieces speak to me as two different political projects: in the former, a vision of the wholesomeness of Malay-Muslim community life; and in the latter, the chaos that entails when the state and religion become contested values. Certainly, one can argue the other way: kampung life can also be nasty, brutish and short; the state, qua its role as legitimate arbiter of violence, can also be seen as a realisation of human order.

While there might not be universal answers for any particular community, these are universal problems. As we grapple with the modern nation-state and its overwhelming power over individuals and communities, it seems every community must constantly renegotiate its position with the state. These are not easy questions to resolve. I struggle with my own lack of ability to figure out clear answers. To that extent, the juxtaposition of two clashing political pieces really beg the question: what do we do with this knowledge? In the meanwhile, we’re fated to live with the violence: within our communities; with our neighbours and possibly within ourselves.

Ho Yi Jian grew up on the edge… of the Malay-speaking and Chinese-speaking lines of Cheras, KL. Harbouring an interest in board game design and art writing, he is currently the media officer for a non-profit advocacy organisation based in PJ.