This year will mark the 50th anniversary of Dasar Kebudayaan Kebangsaan, a notion propagated by Tun Abdul Razak during Kongres Kebudayaan Kebangsaan which aims to act as a guideline in our nation-building process in terms of creating an all-encompassing national identity. Tun Abdul Razak addressed three main principles to achieve this aspiration: 1) A dominant culture based on the foundation of this region, 2) The acceptance of other cultures appropriate for our society (eg. the Chinese and Indian culture), and 3) Islam as a vital driving force in shaping our national culture. 50 years later, it seems appropriate to ask: where are we now in terms of a Malaysian identity, and if there is such a thing as one, does it truly represent us, in our past and present?

In 1648, the Treaty of Westphalia became a momentous turning point in defining modern nation states and would eventually influence the sociological view that nations are the product of shared culture, belief systems and goals, in strictly defined geographical borders. As much as the concept was influential in developing international politics, it is worth criticising that it is largely viewed from a European lens where nationhood is often tied to geography and ethnicity. This is problematic when replicated into the Malaysian society for two main reasons: the cultural roots of pre-colonial Malaya is tied to a larger Nusantara heritage that goes beyond borders of nation states, and modern day Malaysia is a melting pot of diverse ethnicities in which some can be traced back to countries outside of Southeast Asia. The very concept of nation-building implies that national culture is enforced and institutionalised to sustain unity of the population. But how does one define a ‘national culture’ for Malaysia? This country only became a recognised nation-state as a result of decolonisation and this was mostly conditioned to terms laid by the British. For that reason, it should be considered that the roadmap for our nation-building is actually shaped by social institutions made during the colonial era, from a one-dimensional European perspective.

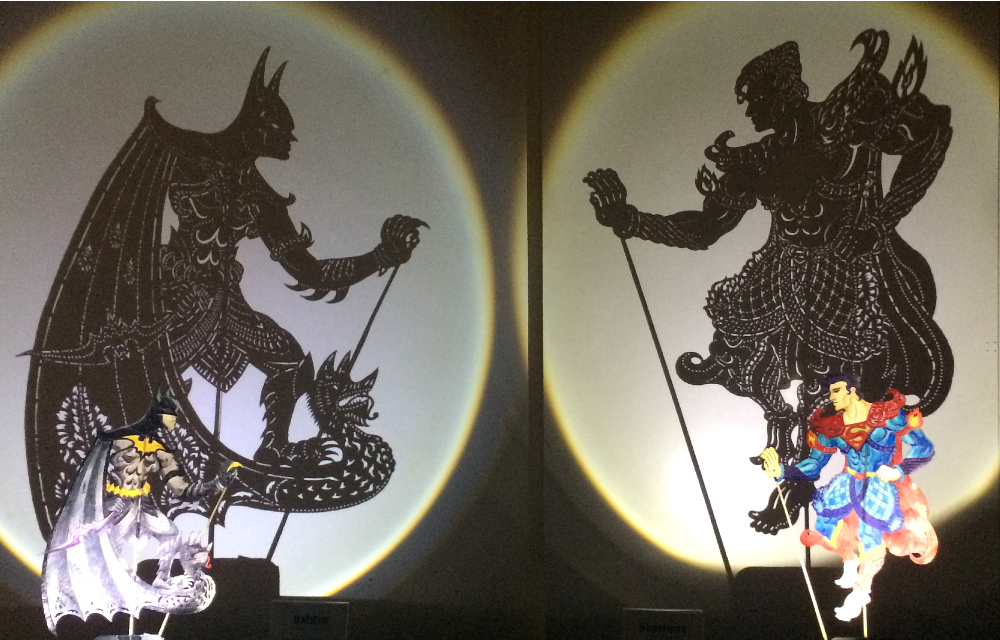

As mentioned before, pre-colonial Malaya was part of the greater Malay Nusantara region where even though it was made up of multiple kingdoms, they were all interconnected by language, belief systems and practices. Through this notion alone, it is difficult to identify a specific historical culture to Malaysia alone as a nation state and therefore almost impossible to define a ‘national identity’ rooted in geography. To add to that, our society had welcomed migrants from our days as a significant maritime trade port, particularly Melaka. In other words, the cultural aspect of Malaysia’s landscape is contributed by this concoction of various ethnicities which have existed for centuries on this land. That being said, Malaysia is not just a multi-racial society — it is in its essence, multi-civilisational.

Ethnic cleavages were further institutionalised when the British administration in Malaya implemented the ‘rule and divide’ policy in which racial groups were strictly separated based on their economic activities. This therefore resulted in a rather interesting racial dynamic where despite there being some form of integration between the ethnic groups in efforts to obtain independence later on, divide was still apparent through dominant race-based political organisations. In regards to this, it can be argued that there was very little grassroots initiative in enhancing an integrated Malayan — later, Malaysian — narrative prior to independence. Even when there was such an effort, such as the short-lived Independence of Malaya Party (IMP), support for it was little compared to the backing for race-specific groups that relied on political leadership to form inter-race alliances. Due to this, the view can be asserted that Malaysia only attempted an organic form of integrated nation-building when the British had left. These initiatives were particularly highlighted during Tun Abdul Razak’s premiership as there was a dire need to engage in social harmony especially after the formation of Malaysia in 1963 and the horrendous event of 13th May in 1969. He was renowned for introducing the New Economic Policy (NEP) which sought to eradicate the economic cleavages between the racial groups. However, the struggle lies in choosing between maintaining the status quo of racial dynamics resulting from colonialism and constitutional provisions, and moving towards a different vision for Malaysia. This is the major dilemma that still exists today which I believe is largely a result of colonialism. That some form of ethnic dominance and superiority needs to be institutionalised to create a unified nation.

However, this claim is not meant to undermine the harmony that Malaysians have enjoyed from our shared experiences but instead, it begs to question if such unity reflects one’s self-conception in regards to being Malaysian. Whilst nationalism and national identity are often tied to a shared political and cultural history, the Malaysian narrative is also heavily shaped from a polarised view of how the nation should move forward. On one hand, there are racial gaps which still exist as a result of decades of systemic culture from the early years of independence, hence necessitating affirmative action. On the other hand, there have been movements highlighting the need to address Malaysia in terms of all of its people as one unit, instead of individual ethnic groups. Revisiting the conceptualisation of a nation which was mentioned earlier on, the issue in Malaysia becomes complex because we indeed share a common history but the question remains if we have all agreed on a common goal for the nation. The problem is rarely in regards to the freedom for expression of individual cultures but it is about the continuous narrative of “us” vs “them”. What should constitute the sense of Malaysian-ness? Where diversity is relished, where do we come together to move forward?

These questions become difficult to answer because the foundation of our nation-building process is largely tied to colonial Eurocentric ideals of what a nation should be. These ideals would generally elevate a specific group of people to represent the values of the whole nation and in the Malaysian context, it would be the Malay race. The situation becomes even more complex as the Malay ethnicity becomes increasingly intertwined with Islamic values, and oftentimes, Arab culture. As Malays are generally seen as representatives of Malaysian identity due to its special position in the constitution, cultures and values that are deemed non-Islamic tend to be in vulnerable positions. Malaysia’s gradual trend towards becoming more Islamist is often argued to be a threat towards the preservation of non/pre-Islamic practices which were defining elements of Malaysian culture back then. This issue therefore strengthens the claim that Malaysia’s nation-building process is over-reliant on the idea that specific cultural values should be elevated to define the national identity.

The question on what values should embody the Malaysian identity seems rhetorical but it ought to be made a discourse to mobilise the nation to where it should be heading. National identity is never meant to be a simplified list with cherry-picked elements and practices that defines a country of 32 million people of diverse cultures, religions and values. The solution should therefore be an umbrella that unifies us through a unique Malaysian narrative whilst still celebrating diversity without having to seek compromise. 50 years since Dasar Kebudayaan Kebangsaan was established, did we successfully grow with its ideals or are we still searching for the answer to what defines us as Malaysia? For this reason, there is a sensible need to review the principles addressed by Tun Abdul Razak to reflect our ever-evolving nation and reshape how we look at our national identity.

As comforting as it is to see increasing awareness amongst grassroots initiatives, discourse and action should also be taken at institutional levels to address this matter. Culture and identity may not seem as tangible and urgent as compared to state security and economic growth, but they hold extremely great value in defining generations of people who call themselves Malaysians.

References:

- Jkkn.gov.my. n.d. Dasar Kebudayaan Kebangsaan | JKKN. [online] Available at: <http://www.jkkn.gov.my/ms/dasar-kebudayaan-kebangsaan> [Accessed 25 January 2021].

- Hirschman, C. (1986). The making of race in colonial Malaya: Political economy and racial ideology. Sociological Forum, 1(2), 330-361. doi: 10.1007/bf01115742

- Mohamad, A., Nasir, B., Yusof, K., Muhamad, N., Safar, A., & Aziz, Y. et al. (2014). Da’wah resurgence and political islam in malaysia. Procedia – Social And Behavioral Sciences, 140, 361-366. doi: 10.1016/

- Embong, A. R. (2002). Malaysia as a multicultural society. Macalester International, 12(1), 10.